The Paths COVID-19 Used To Spread Across Brazil – Super-Spreader Cities, Highways, Hospitals

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 21 June, 2021

- Category:

- Covid

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

Maps of Brazil were used to show the routes of the main longitudinal (AD), transverse (EH), diagonal (IL), radial (MP) and connector (QT) federal highways, as well as the evolution of the geographical distribution of COVID -19 cases on three dates (April 1, June 1, and August 1) and the distribution of COVID-19 deaths on August 1 (D). In total, 26 highways (see text) from all five road categories contributed to about 30% of the spread of COVID-19 throughout Brazil. The numbers of some of these expanding highways are marked in red. Note how many hotspots (red color) for COVID-19 cases exist in micro-regions with cities along major highway routes such as BRs 101, 116, 222, 232, 236, 272, 364, 374, 381, 010, 050, 060, 450 and 465. Although the distributions for COVID-19 cases and deaths were correlated, geographical differences between the two distributions can be seen by comparing them on August 1 (C and D). A color code (see image below) ranks Brazilian micro-regions (each consisting of multiple drags) based on their number of COVID-19 cases and deaths. Credit: Nicolelis, MAL et al. 2021. Scientific Reports, doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92263-3

The impact of super-dispersed cities, highways and intensive care availability in the early stages of Brazil’s COVID-19 epidemic.

A multidisciplinary analysis by a group of Brazilian scientists, published online in the journal Scientific Reports on June 21, 2021, revealed that three major factors were responsible for the geographic distribution of SARS-COV-2 across Brazil, as well as the huge influx of people seeking hospital care. across the country, during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020.

SARS-CoV-2 entered Brazil through the country’s international airports in late February 2020. Mathematical modeling revealed that during the first weeks of March 2020, the “super-dispersed city” of São Paulo, located next to both Brazil’s largest international airport and the country’s busiest highway junction, accounted for more than 85% of the COVID-19 case spread across the country. Brazil. By considering only 16 other distribution cities, the authors were able to explain 98-99% of the cases reported during the first 3 months of the Brazilian pandemic in 2020. Most of this spread of COVID-19 cases resulted from people traveling around the world. the country’s major highways and airspace, which remained open throughout March 2020. For example, a group of 26 major federal highways alone accounted for about 30% of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during this period.

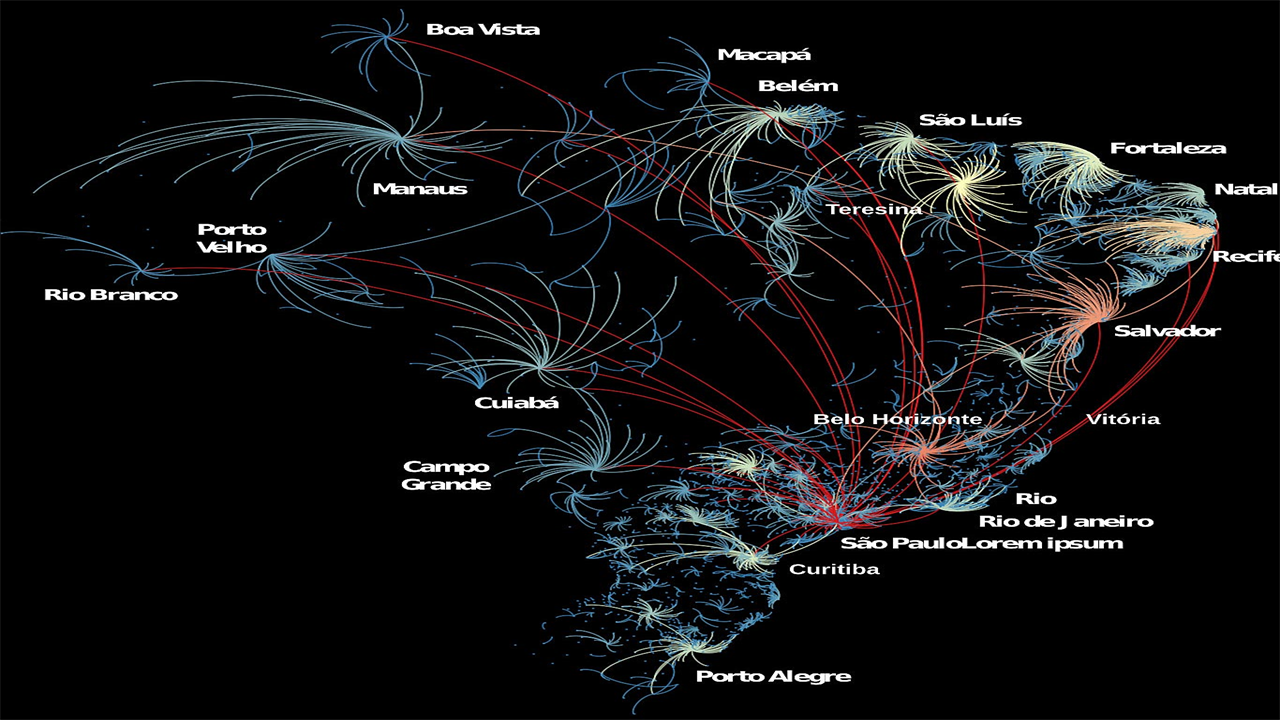

(A) Representation of all “boomerangs” that occurred around major Brazilian capitals (see labels for names) and medium-sized cities across the country. In this map, arcs represent the flow of people from the interior to the capital. The arc color code represents the number of inner cities that sent critically ill patients to hospitals in a capital or medium-sized city; red is the highest number of locations, orange and yellow next, while a smaller number of locations are shown in light blue. Most of the flow of people shown in this graph has taken place via highways. Red arcs probably represent long-haul flow through aircraft. In the Amazon, most of the flow of people to Manaus took place with boats through the Amazon River and its tributaries. Note that São Paulo reappears as the city with the highest boomerang effect, followed by Belo Horizonte, Recife, Salvador, Fortaleza, and Teresina. (B) Lethality and hospitalization data, divided by capital and domestic (for lethality) and resident and non-resident (hospitalization), for a sample of state capitals in all five regions of Brazil. Shades of yellow in the fatality charts represent periods when more deaths occurred inland relative to the capital. In the hospitalization graphs, yellow shading represents periods of increasing admission of people living in rural areas to the main hospital system. The general flow of people from the capital to the interior and back to the capital featured the boomerang effect, targeting the capital’s hospital system. Note that the boomerang effect was ubiquitous across the country and occurred in every Brazilian state. Credit: Nicolelis, MAL et al. 2021. Scientific Reports, doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92263-3

After the emergence of community transmission in the 16 major superspreaders, SARS-CoV-2 cases spread to rural Brazil through the country’s federal and state roads. As the number of cases grew exponentially in the Brazilian interior, critically ill patients from the interior had to be transported to state capitals to access ICU beds, creating a “boomerang effect” that helped skew the distribution of COVID-19 deaths. Therefore, the distribution of COVID-19 deaths began to correlate with the allocation of the country’s highly unequal distribution of intensive care units (ICUs), which is weighted heavily by state capitals.

According to Miguel Nicolelis, one of the authors of the study, “our analysis has clearly shown that if a national lockdown and mandatory traffic restrictions were enforced around Brazil’s major super-dispersed cities, particularly in the city of São Paulo, the impact of COVID-19 in Brazil would be significantly lower during the first wave, but also during the even more damaging second wave that hit the country a year later in the summer of 2021. From June 2020 to June 2021, Brazil went from 50,000 to 500,000 deaths, a tenfold increase in 12 years. months. This alone illustrates the utter failure of the Brazilian federal government to protect Brazilians from the worst humanitarian tragedy in the entire history of the country.”

(A) Distribution of ICU beds across Brazil. The height of the bar is proportional to the number of IC beds in each city. Note how the capitals of the coastal states accumulate the most IC beds in the entire country, while far fewer beds are available in the interior of most states. The city of São Paulo has the largest number of IC beds in the entire country. (B) Superimposition of the COVID-19 mortality distribution (color-coded legend in the lower left corner) on top of the IC bed distribution as seen in (A). For each bar, the height represents the number of ICU beds in a city, while the color represents the number of deaths in that city. Again, the city of São Paulo, which has by far the highest number of ICU beds, has accumulated the highest number of COVID-19-related fatalities, followed by state capitals such as Rio de Janeiro, Fortaleza, Brasilia, Salvador, Manaus, Recife and Belém. The 3D maps were created using the online resources available at http://kepler.gl/. Credit: Nicolelis, MAL et al. 2021. Scientific Reports, doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92263-3

In Brazil, the vast majority of tertiary hospitals, and thus the bulk of intensive care beds, are located in major cities that serve as state capitals, their metropolitan areas, and a handful of mid-sized cities in the interior of each state. As a result of the widespread “boomerang effect” across the country, Brazil experienced the largest increase in hospitalizations in its history, leading to spikes in deaths in any of the cities with a large number of intensive care units. Such a “boomerang flow” was not limited to roads and highways.

For example, in the Amazon rainforest, located in the northern region of Brazil, seriously ill COVID-19 patients from many small riverine communities were transported by all kinds of boats via the major rivers to the two largest Amazon cities, Manaus and Belém. Overall, analysis of the geographic flow of COVID-19 patients showed that São Paulo, the largest Brazilian super-dispersed city, received patients from 464 different cities across Brazil, followed by Belo Horizonte (351 cities), Salvador (332 cities) , Goiânia (258 cities), Recife (255 cities) and Teresina (225 cities). São Paulo was also the city that sent more residents to hospital in other cities (158 cities), followed by Rio de Janeiro (73 cities), Guarulhos (41 cities), Curitiba (40 cities), Campinas (39 cities), Belém (38 cities) and Brasília (35 cities).

In general, cities that were highly connected to the health system’s network, by receiving or sending patients to other cities, also had a higher rate of COVID-19 deaths. Therefore, a significant number of critically ill patients as a result of the “boomerang effect” had to migrate to larger cities for treatment and a significant number of them eventually died there. Combined with the deaths of residents of major cities, the widespread “boomerang effect” contributed decisively to the geographic skew of the distribution of death from COVID-19 across Brazil.

Commenting on the study’s findings, Rafael Raimundo, another author, said that “our analysis has elucidated in detail the mechanisms by which COVID-19 spread rapidly through Brazil. Our findings also indicate that if non-drug measures, such as highway blockades and closures, had been enforced early at the national or even regional level, thousands of lives could have been saved as the COVID-19 pandemic began in Brazil.”

The authors also stressed in their conclusions the fundamental importance of the Brazilian public health system, known as SUS. According to Rafael Raimundo “Without SUS’s public health infrastructure built over the past 40 years, the impact of COVID-19 would certainly be even more devastating. But our data also shows that the magnitude of the “boomerang effect” highlights the need for SUS to install more hospital infrastructure, including more intensive care unit beds, in the Brazilian interior to better serve the rural population and to be of service.”

“Certainly, the widespread absence of adequate hospital infrastructure and health workers in rural Brazil has contributed decisively to a large number of deaths that could have been avoided altogether. But if the Brazilian federal government had responded quickly and correctly to the arrival of SARS-CoV-2, by creating a national scientific task force charged with fighting the pandemic, while setting up a national communication campaign to While a national lockdown was put in place in early March 2020, including roadblocks on major federal and state highways, Brazil would almost certainly have prevented the loss of tens of thousands of lives,” added Miguel Nicolelis.

Reference: “The Impact of Super-Distributed Cities, Highways and Intensive Care Availability in the Early Stages of Brazil’s COVID-19 Epidemic” by Miguel AL Nicolelis, Rafael LG Raimundo, Pedro S. Peixoto and Cecilia S. Andreazzi, June 21 2021, scientific reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-92263-3

The authors of this article were: Miguel AL Nicolelis, Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA, and Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neurosciences, Natal, Brazil, Rafael LG Raimundo, Department of Engineering and Environment and Postgraduate Program in Ecology and Environmental Monitoring (PPGEMA), Center of Applied Sciences and Education, Universidade Federal da Paraíba – Campus IV, Rio Tinto, Paraíba, Brazil, Pedro S. Peixoto, Department of Applied Mathematics, Institute of Mathematics and Statistics, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, and Cecilia S. Andreazzi, Laboratory of Biology and Parasitology of Wild Reservoir Mammals, IOC, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mobility data used in this study was obtained from a collaboration between the Department of Applied Mathematics, Institute of Mathematics and Statistics, University of São Paulo and the company InLoco/Incognia.