The Older You Are, the More Antibodies You Have – Better Protection Against Delta Variant

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 11 November, 2021

- Category:

- Covid

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

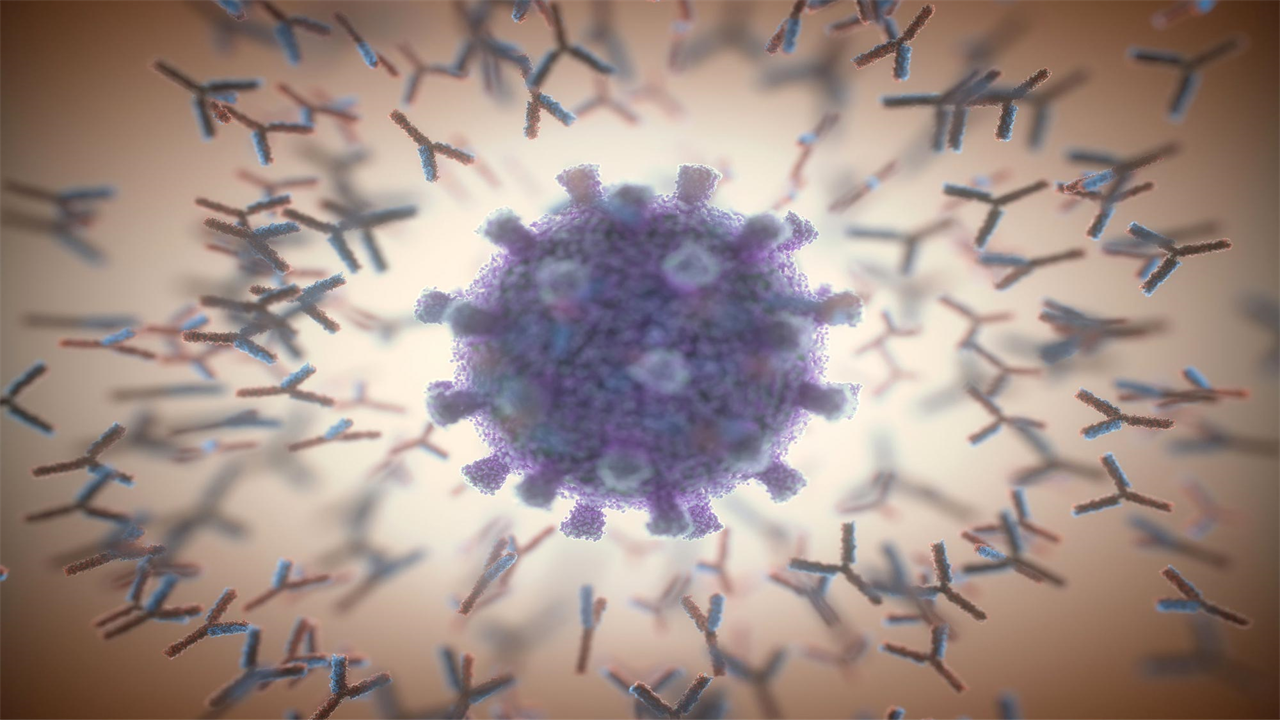

An artistic representation of antibodies surrounding a SARS-CoV-2 particle.

With the rise of SARS-CoV-2 variants worldwide, the spread of the pandemic is accelerating. A research team led by Joelle Pelletier and Jean-François Masson, both professors in the chemistry department of the Université de Montréal, wanted to find out whether natural infection or vaccination caused more protective antibodies to be generated.

In their research recently published in Scientific Reports, they find that those who received the Pfizer BioNTech or AstraZeneca vaccine had antibody levels that were significantly higher than in infected individuals. These antibodies were also effective against the Delta variant, which was not present in Quebec when the samples were collected in 2020.

Masson, a specialist in biomedical instruments, and Pelletier, an expert in protein chemistry, were interested in an underexposed group: people infected with SARS-CoV-2 but not hospitalized as a result of the infection.

32 unhospitalized COVID-19 positive Canadian adults

As a result, 32 unhospitalized COVID-19 positive Canadian adults were recruited through PCR testing 14 to 21 days after diagnosis by the Center Hospitalier de l’Université Laval. This was in 2020, before the Beta, Delta and Gamma variants emerged.

“Anyone who was infected produced antibodies, but older people made more of them than adults under the age of 50,” Masson said. “In addition, there were still antibodies in their blood 16 weeks after diagnosis.”

Antibodies produced after infection by the original, “native” strain of the virus also responded to SARS-CoV-2 variants that emerged in subsequent waves, namely Beta (South Africa), Delta (India) and Gamma (Brazil), but to a lesser extent: a reduction of 30 to 50 percent.

A surprising reaction to the Delta variant

“But the result that surprised us the most was that antibodies produced by naturally infected individuals 50 and older offered a greater degree of protection than adults under 50,” Pelletier said.

“This was determined by measuring the ability of the antibodies to inhibit the interaction of the Delta variant spike protein with the ACE-2 receptor in human cells, which is how we get infected,” he added. to. “We did not see the same phenomenon in the other variants.”

When someone who has had a mild form of COVID is vaccinated, the antibody level in their blood doubles compared to an unvaccinated person infected with the virus. Their antibodies are also better able to prevent spike-ACE-2 interaction.

“But what’s even more interesting,” Masson said, “is that we have samples from a person younger than 49 years of age whose infection did not produce antibodies that inhibit the spike-ACE-2 interaction, unlike vaccination. This suggests that vaccination may protection against the Delta variant increases in people previously infected with the native strain.”

Both scientists believe that more research needs to be done to determine the best combination for maintaining the most effective level of antibodies that respond to all variants of the virus.

Reference: “Cross-reactivity of antibodies from non-hospitalized COVID-19-positive individuals to the native, B.1.351, B.1.617.2, and P.1 SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins” by Maryam Hojjat Jodaylami, Abdelhadi Djaïleb, Pierre Ricard, Étienne Lavallée, Stella Cellier-Goethebeur, Megan-Faye Parker, Julien Coutu, Matthew Stuible, Christian Gervais, Yves Durocher, Florence Desautels, Marie-Pierre Cayer, Marie Joëlle de Grandmont, Samuel Rochette, Danny Brouard, Sylvie Trottier , Denis Boudreau, Joelle N. Pelletier, and Jean-Francois Masson, Oct. 26, 2021, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-00844-z

The study was conducted in collaboration with Université Laval, the Center hospitalier de l’Université Laval, Héma-Québec and the National Research Council of Canada. It was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the National Research Council of Canada’s Pandemic Response Challenge Program, and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.