Many COVID-19 Patients Produce Immune Responses Attacking Their Body’s Own Tissues and Organs

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 13 June, 2021

- Category:

- Covid

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

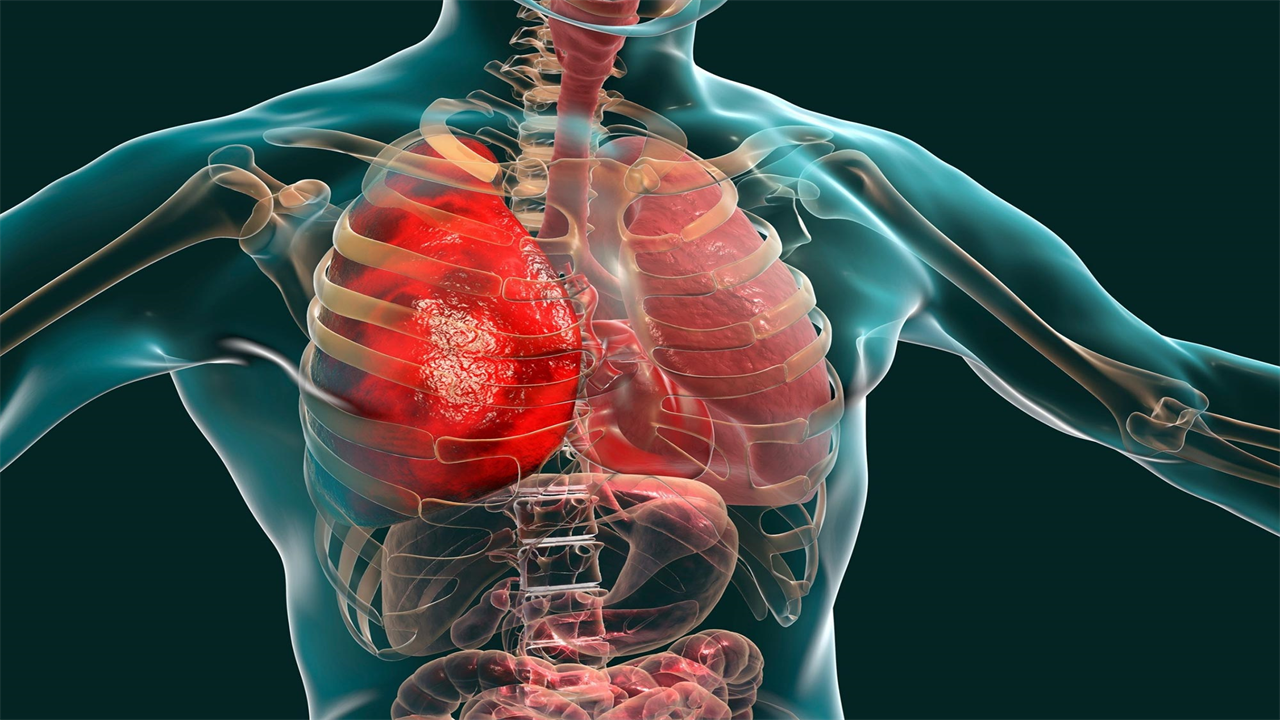

A study led by the University of Birmingham, funded by the UK Coronavirus Immunology Consortium, has shown that many patients with COVID-19 produce immune responses against their body’s own tissues or organs.

COVID-19 has been associated with a variety of unexpected symptoms both at the time of infection and for many months afterwards. It’s not entirely clear what causes these symptoms, but one possibility is that COVID-19 triggers an autoimmune process in which the immune system is misdirected to attack itself.

The study, published June 3, 2021, in the journal Clinical & Experimental Immunology, examined the frequency and types of common autoantibodies produced in 84 individuals who had either severe COVID-19 at the time of testing or in the recovery period after both severe. COVID-19 and people with milder illness who did not require hospitalization. These results were compared with a control group of 32 patients who were in intensive care for a reason other than COVID-19.

An autoantibody is an antibody (a type of protein) produced by the immune system that targets one or more of the individual’s own proteins and can cause autoimmune diseases. Infection can lead to autoimmune disease in some cases. Early data suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause long-term autoimmune complications and there are reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a number of autoimmune diseases, including Guillain-Barre syndrome .

Supported by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the study found higher numbers of autoantibodies in the COVID-19 patients than the control group and that these antibodies lasted for up to six months.

Non-COVID patients showed a diverse pattern of autoantibodies; by contrast, the COVID-19 groups had a more limited panel of autoantibodies, including skin, skeletal muscle, and heart antibodies.

The authors also find that people with more severe COVID-19 are more likely to have an autoantibody in their blood.

First author Professor Alex Richter, from the University of Birmingham, explains: “The antibodies we have identified are similar to those that cause a number of autoimmune diseases of the skin, muscle and heart.

“We don’t yet know whether these autoantibodies definitely cause symptoms in patients and whether this is a common phenomenon after many infections or just after COVID-19. These questions will be addressed in the next part of our study.”

Senior author Professor David Wraith, from the University of Birmingham, adds: “In this detailed study of a range of different tissues, we have shown for the first time that COVID-19 infection is linked to the production of selective autoantibodies. More work is needed to determine whether these antibodies contribute to the long-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection and therefore could be targets of treatment.”

Professor Paul Moss, Principal Investigator of the UK Coronavirus Immunology Consortium and Professor of Hematology at the University of Birmingham, added: “This is an interesting study that reveals new insights into a possible autoimmune component to the effects of COVID-19. Research like this has been made possible by the massive concerted efforts of those who are part of the UK Coronavirus Immunology Consortium. This study is another important step towards real improvements in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 for patients.”

The study participants were divided into four cohorts:

Group one: 32 people sampled during their stay in intensive care for reasons other than COVID-19. 41% of the individuals had autoantibodies. In this group there were many different causes of their disease (more than half were pneumonia) and autoantibodies were found against almost all the different autoantigens examined, indicating a more random distribution. Group two: 25 individuals sampled during their stay in intensive care after a diagnosis of severe COVID-19. 60% had autoantibodies. Of those who tested positive for autoantibodies, 41% had epidermal (skin) antibodies, while 17% had skeletal antibodies. Group Three: 35 individuals admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 survived and were sampled three to six months later during routine outpatient follow-up. 77% of the individuals had autoantibodies. Of those who tested positive for autoantibodies, 19% had epidermal (skin) antibodies, 19% had skeletal antibodies, 28% had heart muscle antibodies; and 31% had smooth muscle antibodies. Group Four: 24 health professionals sampled one to three months after mild to moderate COVID-19 that did not require hospitalization. 54% of the individuals had autoantibodies. In those who tested positive for autoantibodies, it was against only four autoantigens: 25% had epidermal (skin) antibodies; 17% had smooth muscle antibodies; 8% had anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic (ANCA) antibodies targeting a type of human white blood cells; and 4% had gastric parietal antibodies associated with autoimmune gastritis and anemia.

Reference: “Assessing the Prevalence of Common Tissue-Specific Autoantibodies Following SARS CoV-2 Infection” by Alex G. Richter, Adrian M. Shields, Abid Karim, David Birch, Sian E. Faustini, Lora Steadman, Kerensa Ward , Timothy Plant, Gary Reynolds, Tonny Veenith, Adam F. Cunningham, Mark T. Drayson, and David C. Wraith, June 3, 2021, Clinical & Experimental Immunology.

TWO: 10.1111 / cei.13623

The University of Birmingham is ranked in the top 100 institutions in the world and its work brings people from all over the world to Birmingham, including researchers and teachers and more than 6,500 international students from nearly 150 countries.

The UK Coronavirus Immunology Consortium is bringing together 20 UK immunology centers of expertise to explore how the immune system interacts with SARS-CoV-2 to help us improve patient care and develop better diagnostics, treatments and vaccines against COVID-19. It is jointly funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and supported by the British Society for Immunology.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the nation’s largest funder of health and care research. The NIHR:

Funds, supports and delivers high-quality research that benefits the NHS, public health and social care Engages and engages patients, carers and the public to improve the reach, quality and impact of research Attracts, trains and supports the best researchers to tackle the complex health and care challenges of the future Invests in world-class infrastructure and skilled workforces to translate discoveries into improved treatments and services Partners with other public funders, charities and industry to increase the value of research for patients maximize and the economy

The NIHR was established in 2006 to improve the health and prosperity of the nation through research, and is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. In addition to its national role, the NIHR supports applied health research for the direct and primary benefit of people in low- and middle-income countries, with the help of UK government assistance