Even Mild Cases of COVID-19 Leave a Mark on the Brain – And It’s Not Yet Clear How Long It Lasts

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 3 October, 2021

- Category:

- Covid

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

The new findings, while preliminary, raise concerns about the potential long-term effects of COVID-19.

With more than 18 months of the pandemic in the rearview mirror, researchers have steadily gathered new and important insights into the effects of COVID-19 on the body and brain. These findings raise concerns about the long-term effects the coronavirus may have on biological processes such as aging.

As a cognitive neuroscientist, my previous research has focused on understanding how normal brain changes associated with aging affect people’s ability to think and move, especially in middle age and beyond. But as more evidence emerged showing that COVID-19 could affect the body and brain months or more after infection, my research team became interested in exploring how it could also affect the natural aging process.

Watching the brain’s response to COVID-19

In August 2021, a preliminary but large-scale study of brain changes in people who had had COVID-19 attracted considerable attention within the neuroscience community.

In that study, researchers relied on an existing database called the UK Biobank, which contains brain imaging data from more than 45,000 people in the UK dating back to 2014. This means – crucially – that there was baseline data and brain imaging from all those people from before the pandemic.

The research team analyzed the brain imaging data and then brought those diagnosed with COVID-19 back for additional brain scans. They compared people who had experienced COVID-19 with participants who had not, carefully matching the groups for age, gender, baseline test date and study location, as well as general risk factors for disease, such as health variables and socioeconomic status.

The team found clear differences in gray matter — which is made up of the cell bodies of neurons that process information in the brain — between those infected with COVID-19 and those who didn’t. In particular, gray matter thickness in brain regions known as the frontal and temporal lobes was reduced in the COVID-19 group, in contrast to the typical patterns seen in the group that did not have COVID-19. to experience.

In the general population, it is normal to see some change in gray matter volume or thickness over time as people age, but the changes were greater than normal in those infected with COVID-19.

Interestingly, when the researchers separated the individuals who were seriously ill enough to require hospitalization, the results were the same as for those who had experienced milder COVID-19. That is, people infected with COVID-19 showed a loss of brain volume even when the disease was not severe enough to require hospitalization.

Finally, researchers also examined changes in performance on cognitive tasks and found that those who contracted COVID-19 were slower at processing information than those who did not.

While we must interpret these findings with caution pending formal peer review, the large sample size, pre- and post-disease data in the same people, and careful matching with people who had not had COVID-19 made this preliminary work particularly valuable.

What do these changes in brain volume mean?

Early on in the pandemic, one of the most common reports of people infected with COVID-19 was the loss of taste and smell.

Some COVID-19 patients have experienced the loss or reduction of their sense of smell.

Notably, the brain regions the UK researchers found were affected by COVID-19 are all related to the olfactory bulb, a structure at the front of the brain that relays signals about odors from the nose to other brain regions. The olfactory bulb has connections to areas of the temporal lobe. We often talk about the temporal lobe in the context of aging and Alzheimer’s disease, because that’s where the hippocampus is located. The hippocampus probably plays a key role in aging, given its involvement in memory and cognitive processes.

The sense of smell is also important for Alzheimer’s research, as some data has suggested that those at risk for the disease have a reduced sense of smell. While it is far too early to draw any conclusions about the long-term effects of these COVID-19-related changes, it is vital to explore possible links between COVID-19-related brain changes and memory, especially given the regions involved and their importance. in memory and Alzheimer’s disease.

Looking forward

These new findings raise important but unanswered questions: What do these post-COVID-19 brain changes mean for the process and pace of aging? And does the brain recover to some degree from a viral infection over time?

These are active and open areas of research, some of which we are starting to do in my own lab in conjunction with our ongoing research on brain aging.

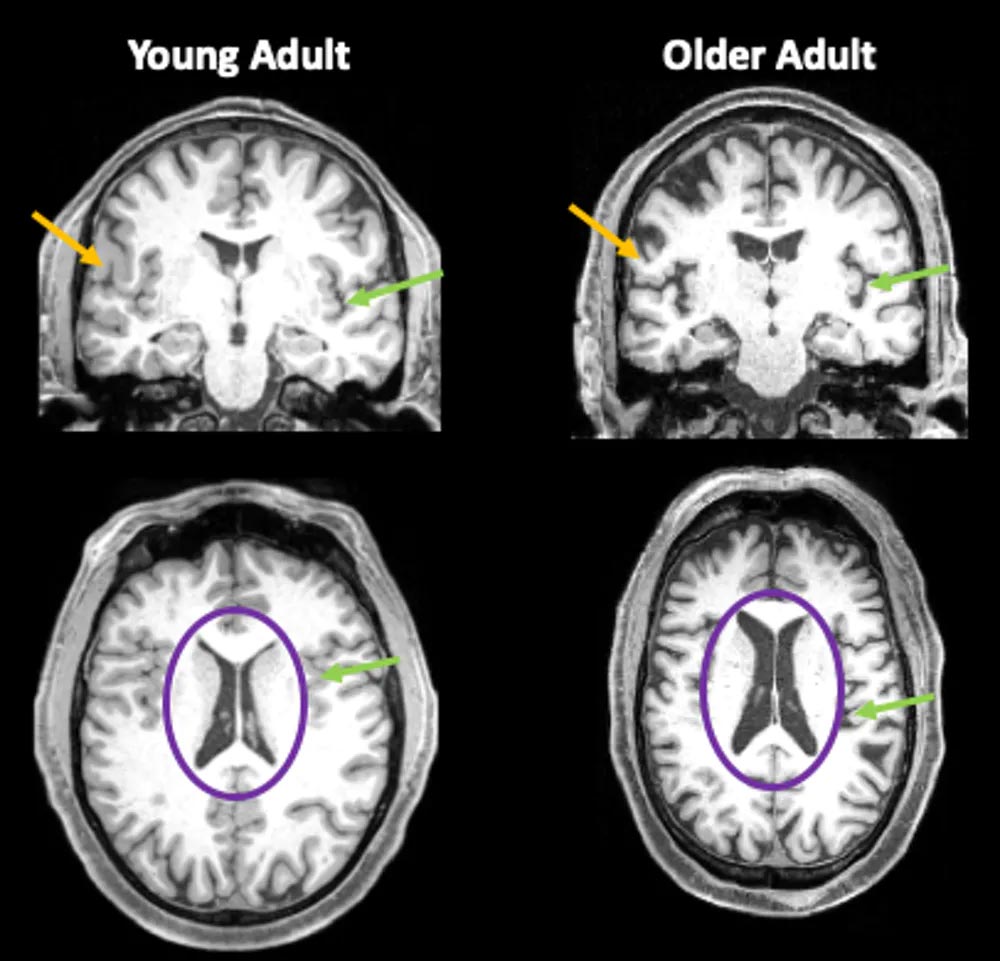

Brain images of a 35-year-old and an 85-year-old. Orange arrows show the thinner gray matter in the older individual. Green arrows point to areas where there is more space filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) due to reduced brain volume. The purple circles mark the ventricles of the brain, which are filled with CSF. In older adults, these fluid-filled areas are much larger. Credit: Jessica Bernard

Our lab’s work shows that as people age, the brain thinks and processes information differently. In addition, we have observed changes over time in the way people’s bodies move and how people learn new motor skills. Several decades of work have shown that older adults have a harder time processing and manipulating information — such as updating a mental shopping list — but they typically retain their knowledge of facts and vocabulary. With regard to motor skills, we know that older people still learn, but at a slower rate than younger people.

When it comes to brain structure, we usually see a decrease in brain size in adults over the age of 65. This decrease is not only localized in one area. Differences can be seen in many brain regions. There is also typically an increase in cerebrospinal fluid filling the space due to the loss of brain tissue. In addition, white matter, the insulation on axons — long cables that carry electrical impulses between nerve cells — is also less intact in older adults.

As life expectancy has increased in recent decades, more and more people are aging. While the goal is for everyone to live a long and healthy life, even in the best-case scenario of aging without illness or disability, older adulthood brings about changes in how we think and move.

By learning how all these puzzle pieces fit together, we can unravel the mysteries of aging so that we can help improve the quality of life and functioning of aging individuals. And now, in the context of COVID-19, it will help us understand to what extent the brain can also recover after illness.

Written by Jessica Bernard, associate professor, Texas A&M University.

This article was first published in The Conversation.