COVID-19 Patients Can Be Categorized Into Three Groups – Here Are the 3 Phenotypes

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 17 April, 2021

- Category:

- Covid

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

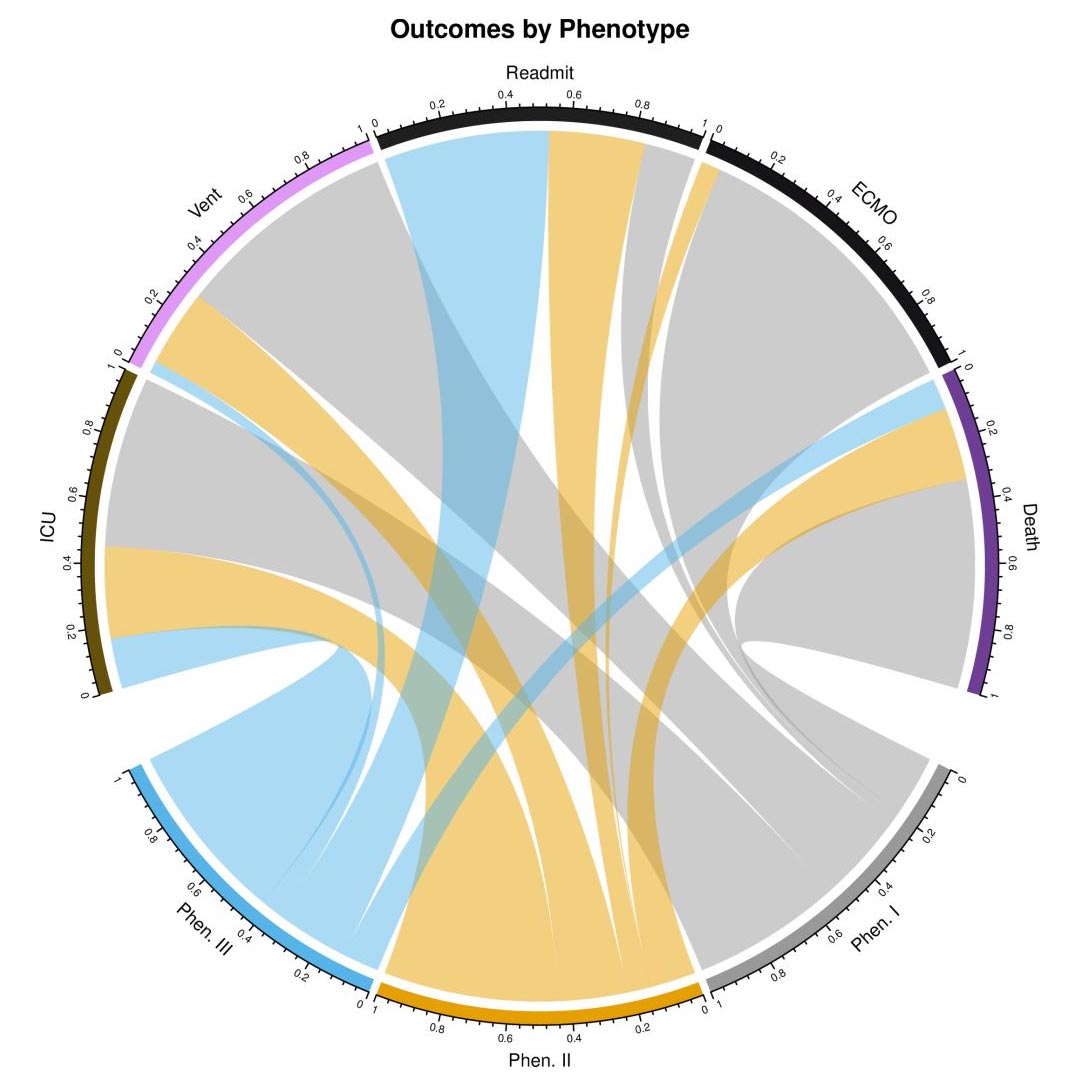

Clinical Results by Phenotype. Chord diagram illustrates the prevalence of clinical outcomes (% observed) for the three clinical phenotypes. Abbreviations: ICU (intensive care); Vent (mechanical ventilation); Readmission (readmission to hospital or ICU); ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation). Credit: Lusczek et al, 2021, PLOS ONE (CC-BY 4.0)

Phenotypes I, II and III show different characteristics and show unfavorable, normal and favorable clinical results, respectively.

In a new study, researchers identify three clinical COVID-19 phenotypes, reflecting patient populations with different co-morbidities, complications, and clinical outcomes. The three phenotypes are described in a paper published this week in the open access journal PLOS ONE 1st, authors Elizabeth Lusczek and Nicholas Ingraham of the University of Minnesota Medical School, USA, and colleagues.

COVID-19 has infected more than 18 million people and has resulted in more than 700,000 deaths around the world. Emergency care presentation varies widely, suggesting that different clinical phenotypes exist and, more importantly, that these different phenotypic presentations may respond differently to treatment.

In the new study, researchers analyzed electronic health records (EHRs) from 14 hospitals in the Midwestern United States and 60 primary care clinics in the state of Minnesota. Data were available from 7,538 patients with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 between March 7 and August 25, 2020; 1,022 of these patients had to be hospitalized and included in the study. Data about each patient includes co-morbidity, medications, lab values, clinic visits, hospitalization information, and patient demographics.

Most of the patients enrolled in the study (613 patients, or 60 percent), showed what the researchers called “phenotype II.” 236 patients (23.1 percent) presented with “phenotype I” or the “unwanted phenotype”, which was associated with the worst clinical outcomes; these patients had the highest level of haematological, renal and cardiac comorbidity (all p <0.001) and were more likely to be non-white and non-English speaking. 173 patients (16.9 percent) presented with "phenotype III" or the "favorable phenotype", which was associated with the best clinical outcomes; surprisingly, despite the lowest complication rate and mortality, patients in this group had the highest rate of respiratory comorbidities (p = 0.002) and a 10 percent greater risk of hospitalization compared to the other phenotypes. Overall, phenotypes I and II were associated with 7.30-fold (95% CI 3.11-17.17, p <0.001) and 2.57-fold (95% CI 1.10-6, 00, p = 0.03) increases in risk of death relative to phenotype III.

The authors conclude that phenotype-specific medical care could improve COVID-19 outcomes, and suggest that future research is needed to determine the usefulness of these findings in clinical practice.

The authors add, “Patients do not suffer from COVID-19 in a uniform manner. By identifying similar affected groups, we not only improve our understanding of the disease process, but it also allows us to accurately target future interventions towards patients at the highest risk. “

Reference: “Characterizing COVID-19 Clinical Phenotypes and Associated Co-morbidities and Complication Profiles” by Elizabeth R. Lusczek, Nicholas E. Ingraham, Basil S. Karam, Jennifer Proper, Lianne Siegel, Erika S. Helgeson, Sahar Lotfi-Emran, Emily J Zolfaghari, Emma Jones, Michael G. Usher, Jeffrey G. Chipman, R. Adams Dudley, Bradley Benson, Genevieve B. Melton, Anthony Charles, Monica I. Lupei, and Christopher J. Tignanelli, March 31, 2021, PLoS ONE.

DOI: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0248956

Funding: 1. NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute T32HL07741 (NEI) 2. This research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), grant K12HS026379 ( CJT) and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002494. 3. NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute T32HL129956 (JP, LS) The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.