A Virologist Explains Each COVID Variant

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 26 April, 2021

- Category:

- Covid

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

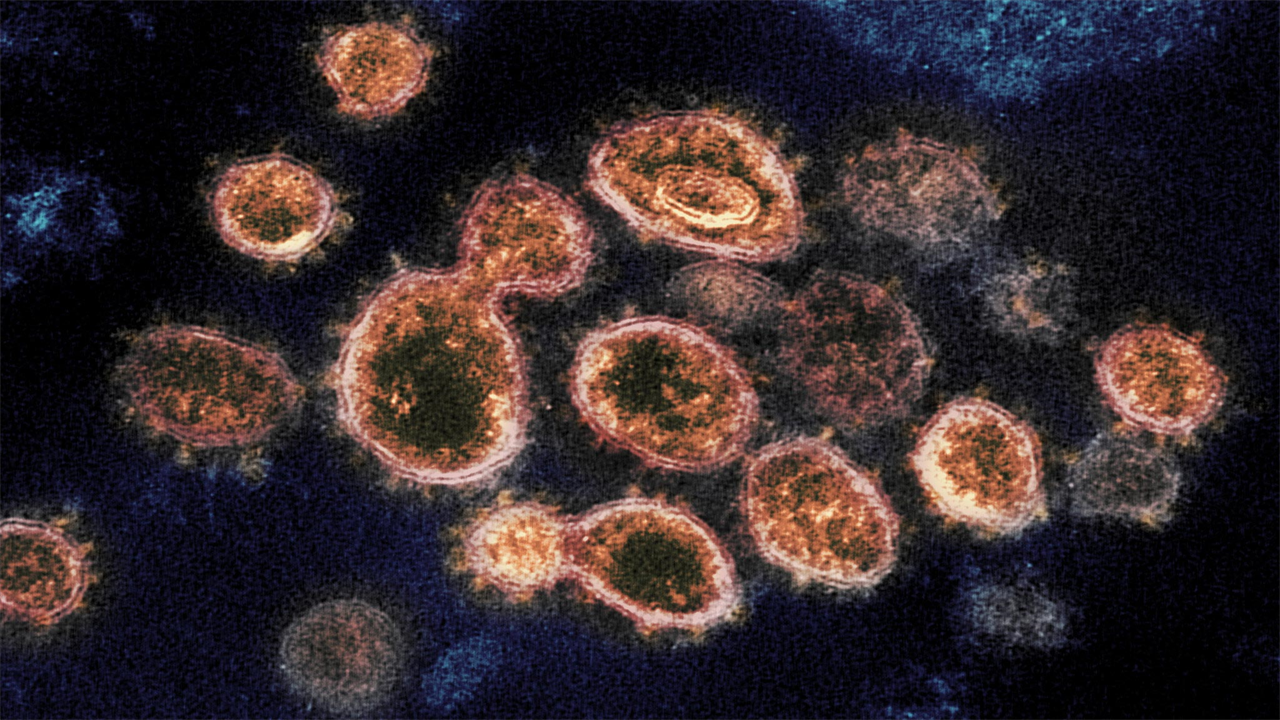

The virus that causes COVID-19, called SARS-CoV-2, is shown here in an electron microscope image. Credit: NIAID-RML

Australia has recently seen SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) escape the quarantine of hotels several times, including in Brisbane, Perth and Melbourne.

These incidents were especially concerning because they involved people infected with ‘variants’ of the virus.

But what exactly are these variants and how concerned should we be?

What is a variant?

Viruses cannot replicate and spread themselves. They need a host, and they need to hijack the host’s cells to replicate. When they replicate in a host, they face the challenge of duplicating their genetic material. For many viruses this is not an exact process and their descendants often contain errors – meaning they are not exact copies of the original virus.

These errors are called mutations and viruses with these mutations are called variants. These mutations often do not affect the biological properties of the virus. That is, they have no effect on how the virus replicates or causes disease.

Some mutations can reduce the virus’ ability to multiply and / or transfer. Variants with such mutations are quickly lost from the viral population.

Occasionally, however, variants appear with a beneficial mutation, one that means it is better at replicating, transmitting, and / or evading our immune systems. These variants have a selective advantage (biologically they are “fitter” than other variants) and can quickly become the dominant viral strain.

There is some concern that we are seeing a growing number of variants with beneficial mutations that contribute to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here is an overview of the three main variations you may have heard about in the media.

The ‘British variant’ – B.1.1.7

This variant was first discovered in the United Kingdom at the end of 2020. It has a large number of mutations, many of which involve the virus’s spike protein, which helps the virus enter human cells.

It has quickly spread across the UK since its emergence, and to at least 70 other countries, including Australia.

The fact that it has spread so quickly and quickly replaced other circulating variants suggests that it has some sort of selective advantage over other variants.

After examining the evidence surrounding the new variant, the UK New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) concluded that it “had moderate confidence” that the variant is significantly more contagious than other variants.

This may be the result of one of the mutations in the variant spike protein – a mutation called “N501Y”. A preprint manuscript, uploaded last month and not yet peer-reviewed, found that N501Y is associated with increased binding of the virus to a receptor found on the surface of many of our cells called “ACE2”. This could mean that the variant enters our cells even more efficiently.

Although the variant was not initially associated with more severe COVID symptoms, more recent data has led NERVTAG to conclude that there is “a realistic possibility” that infection with the variant is “associated with an increased risk of death” compared to non-B .1.1. 7 viruses.

However, the group recognized that there are limitations to the data available and that this remains a changing situation.

The ‘South African variant’ – B.1.351

This variant was first discovered in Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa, in October 2020. Since then, it has been found in more than 30 countries.

Like the UK variant, it quickly outpaced other SARS-CoV-2 variants in South Africa. It now accounts for more than 90% of South Africa’s SARS-CoV-2 samples undergoing genetic sequencing.

Like the British variant, it also has the N501Y mutation in the spike protein, which means it is more efficient in accessing our cells to replicate. This may help explain its rapid spread.

It also includes several other related mutations. Two of these, called “E484K” and “K417N”, are bad news for our immune system. They can decrease the degree of binding of our antibodies to the virus (although this is also based on pre-printed data awaiting peer review).

But there is no evidence yet to suggest that the South African variety is more deadly than the original varieties.

The ‘Brazilian variant’ – P.1

This variant was first discovered in Japan with a group of Brazilian travelers in January 2021.

It is now common in the Brazilian state of Amazonas and has been detected in South Korea and the United States, among others.

Like the South African variant, the Brazilian variant has the spike protein mutations N501Y, E484K, and K417N (as well as numerous other mutations).

While there is no evidence that this variant causes more serious disease, there is concern that it may have triggered a wave of re-infections in Manaus, the largest city in Amazonas, thought to have “herd immunity” in October last year. reached.

What does this mean for vaccines?

Major vaccine developers are testing the efficacy of their vaccines against these and other variants. In general, the currently licensed vaccines offer relatively good protection against the British variant.

But recent Phase 2/3 data from both Novavax and Johnson & Johnson suggests reduced protection against the South African variety. The Oxford / AstraZeneca vaccine group also published data suggesting that the vaccine provides only minimal protection against mild to moderate disease caused by this variant.

However, it is important to recognize that reduced protection does not mean that there is no protection at all, and that data is still emerging.

In addition, many vaccine manufacturers are now investigating whether modifications to the vaccines can improve their performance against the emerging variants.

The message is that variants will appear, and we need to monitor their spread closely. However, there is all evidence that we can adapt our vaccine strategies to protect against these and future variants.

Written by Kirsty Short, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland.

Originally published on The Conversation.